Hello, I thought I'd quickly send you this short biography below to honour the memory of freind Duncan who just passed away. I visited him again at home just last month (October) driving North on my way back home up to Stromness Orkney. I'm happy we caught up again, though he was poorly, coughing much more than usual. We'd told each other stories, riddles and jokes and bantered. between cups of tea. We both met each other when we were performing together at a storytelling festival a few years ago, then I drove us both home in my van back up to Scotland, singing to each other to keep good company all the way. I'm going to have a wee whisky now in his memory.....Health and joy....to you...too, hoping you're well,

Cheers for now

love from Rory (McLeod)

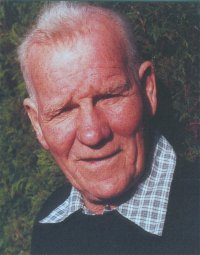

Duncan Williamson

Teller of Scots travellers' tales

Published: 13 November 2007

Duncan James Williamson, storyteller, singer and writer: born Furnace, Argyllshire 11 April 1928; married first Jeanie Townsley (died 1971; three sons, four daughters), second 1976 Linda Headlee (one son, one daughter), (one daughter by Martha Stewart); died Kirkcaldy, Fife 8 November 2007.

The story-teller and singer Duncan Williamson was one of the greatest voices of Scots traveller culture, a name to speak in the same breath as the highest of the high, such as Lizzie Higgins, Jeannie Robertson, Stanley Robertson, Belle Stewart and Sheila Stewart. In his radio history of storytelling, Something Understood: a chain of voices, broadcast on Radio 4 in 2005, Hugh Lupton recalled of Williamson:

It was Duncan who told me that when you tell a story, or sing a song, the person you heard it from is standing behind you. When that person spoke, he, in turn, had a teller behind him, and so on, back and back and back. I love this idea, the story has to speak to its own time, but the teller has also to be true to the chain of voices that inform him or her.

Williamson kept a covenant with those chains of voices - known and unknown - that had spoken down the generations. Still, he was born into a culture that values traditional knowledge and skills. Wonder stories, trickster tales, nonsense doggerel, riddles and ballads about bloodletting, dark deeds and revenge, held his people in campfire thrall. The supernatural figured prominently. Without spoiling the ending, Williamson's "Tailor and the Skeleton" concerns stitching together a body. Maybe, generations back, this unhallowed tale of a modern Prometheus flickered through Mary Shelley's mind in the 1800s.

"Tam Lin" - a real hand-me-down, whether through Robert Burns's The Scots Musical Museum or Francis J. Child's The English and Scottish Popular Ballads or recordings by Fairport Convention or Anne Briggs - reveals the world of faery beyond the firelight. Williamson recorded his version of "Tam Lin" for Put Another Log on the Fire: songs and tunes from a Scots traveller (1994). He took what had been handed to him and turned it into his own. As storytellers should, he took it to new places.

Duncan Williamson was a Scots traveller - travellers are a historically nomadic people separate to gypsy or Romany people, though they too know about prejudice and vilification. The seventh of 16 children, he was widely reported to have born in a bow tent by Loch Fyne in Argyll, though this may well be a romantic construct.

In his preface to Williamson's A Thorn in the King's Foot: folktales of the Scottish travelling people (1987), the Scots folklorist Hamish Henderson records that Duncan's mother was Betsy Townsley and that his "travelling basketmaker and tinsmith" father was Jock Williamson. Both were unlettered, but steeped in the oral transmission of traveller lore in all its variety. Piping, singing and storytelling was in Duncan's genes. Like many traveller families, they were Roman Catholics.

After leaving school at 14, Duncan Williamson became apprentice to a stonemason and drystone dyker, Neil MacCallum, in Auchindrain in Argyll. MacCallum told stories in English with Scots Gaelic punctuations. Williamson's stories would cover similar linguistic terrain, but with traveller "cover-tongue", or cant, interspersed for good measure.

Inevitably, he took to the road, obtaining agricultural work here, learning horse-dealing there, picking up songs and stories as he went, overlaying the versions he knew with new ones to make them wholly his own. Travellers were known as the "Summer Walkers" in many parts and earned money from seasonal work like freshwater pearl-fishing or berry-picking. Williamson's autobiography, The Horsieman: memories of a traveller, 1928-1958 (1994), tells tales of horse-whispering from another age.

In the mid-1950s, collectors from the School of Scottish Studies hit the mother-lode when in 1955 Henderson "discovered" the singer Jeannie Robertson - hailed as the greatest traditional Scots ballad singer of her day - and in the same year Maurice Fleming discovered the Stewarts of Blair. Within a 12-month the School was discovering so many folktales that the School's Calum MacLean argued prioritising their resources from ballad- and song-collecting to story-collecting. Yet, as Henderson wrote, the man

who was in many ways to turn out possibly the most extraordinary tradition-bearer of the whole traveller tribe had not at that time emerged above the horizon [namely] Duncan Williamson, who in 1956 was only 28 and therefore a youngster compared to many of the informants.

Helen Fullerton, an activist for traveller rights, was the first collector to tape Duncan Williamson, having got to his mother and several of his siblings in 1958. She finally met him in 1967 on one of his visits to his mother. She taped original poetry, songs and ballads. Afterwards, she tipped off the collector Geordie MacIntyre, which led to further recordings that year. The following year, Williamson appeared at the Blairgowrie Folk Festival, organised by the Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland. The TMSA's founder Pete Shepheard would release Williamson's audio-tape Mary and the Seal and Other Folktales on his Springthyme label in 1986.

Williamson went on to international recognition, especially as a storyteller, appearing on literary and folk-music billings. His books documenting traveller life and lore included The Broonie, Silkies and Fairies: travellers' tales (1985), The Genie and the Fisherman, and Other Tales from the Travelling People (1991) and his highly recommended Horsieman. He recorded extensively, appearing most recently on Travellers Tales, Volumes 1 and 2, recorded by Mike Yates and released on his Kyloe label in 2002.

Academic archives holding Williamson's work include the School of Scottish Studies at Edinburgh University, the Center for Appalachian Studies and Services at East Tennessee State University, and the Scottish Storytelling Centre in Edinburgh.

Ken Hunt

From The Times

November 16, 2007

Duncan Williamson

Memerising Scottish storyteller who had a huge repertoire of tales from his nomadic youth among the travelling families

Duncan Williamson was one of the most celebrated storytellers in Scotland. His fame became international when he appeared at storytelling festivals in North America and Australasia and he published many books and recordings of his stories.

Duncan Williamson was born to a travelling family, "under a tree" as he told it, on the shores of Loch Fyne, near Furnace, Argyll, in 1928.

Life in a traveller's bow tent with 15 brothers and sisters was hard in the 1930s, and he would recall "sitting in school pure starving hungry" - so hungry he could not heed the teacher but he knew he had to sit there and put in the legal number of attendances or he would not have the real life of travelling the summer road in horse and wagon with his family. That road would take him to the community of pipers, ballad singers and storytellers that fed in him the passions that were to drive his entire life.

But it was closer to home that these passions began, from his father, uncles and two grannies.

"My wee granny was the best thing ever happened to me," he recalled. His wee granny, Belle, 5ft 2inches tall, was a brilliant storyteller, and as a little boy he determined to be as good as she was. His big granny, 6ft 2in "like a warrior lady", could stop a whole street with the power and beauty of her singing.

The course of his life was set. Travelling the road, working with shepherds, drystone dykers, berry-pickers, fisher folk, cattlemen, moving from the Western Islands to the East Coast harbour towns he gathered stories and stored them in the extraordinary library of his mind.

He left home equipped with two educations: the brief, strict curriculum of the Furnace School that, however, gave him a love of the great British poets, and the education from his family and the travelling people. By the age of 13 he could handle axe and cross-saw, build dykes, dig peats, survive on the fare of river, shore and countrysides, tell a story and sing a song. This life he would later describe in his autobiography, The Horsieman - Memories of a Traveller (1994).

As a young man he married a traveller-lass, Jean Townsley, and together with horse, wagon and tent they took to the road, taking work wherever he could find it.

In the early 1960s Williamson's life changed. He was "discovered" by the School of Scottish Studies and began to sing in Glasgow with the folk luminaries of the day.

After his wife died in 1971, he met another crusading spirit, Linda Hedley, an American student. She recorded his songs, became his wife and, living with him and their two children in the traveller's tent, discovered his huge repertoire of stories. She convinced him that they should be published, and in Stephanie Wolfe-Murray, of the publisher Canongate, they found an enthusiastic advocate. Fourteen books, a tiny morsel of his reputed 3,000 stories followed, and invitations flowed in from around the world.

It was in the telling of his stories that Williamson's genius glowed brightest. Hamish Henderson, the greatest Scottish folk-collector and himself a legendary figure, was quick to recognise his unique qualities of singer and storyteller: "Duncan Williamson," he said, "is the Scottish folk traditions in one man."

It was not Williamson's huge repertoire of story and song that made him one of the world's best-known storytellers, it was the sheer storm force of his being, a force that expressed itself in a tireless generosity, a lavish giving. The old Celtic saying says of the generosity of Finn McCool, "If the leaves of the trees were gold / And the waves of the sea silver / Finn would have given them all away", and Williamson was his spiritual descendant. From Alaska to Australia pilgrims and story enthusiasts came to his ever-open door.

Where two or three were gathered together, for Williamson it was a ceilidh, a night-long feast of story and song. Even if it was only one stranger visiting, Williamson would give him or her his full intent attention, dispensing from his huge purse of tales and songs till the sun shone out of the morning.

For him a story was the greatest gift - "stories was wir education" - and he gave freely.

Williamson is survived by his wife, Linda, and his ten children.

Duncan Williamson, Scottish storyteller, was born on April 11, 1928. He died from the effects of a stroke on November 8, 2007, aged 79

No comments:

Post a Comment